Is Germany Saving or Harming Itself with Its Changing Weather Patterns?

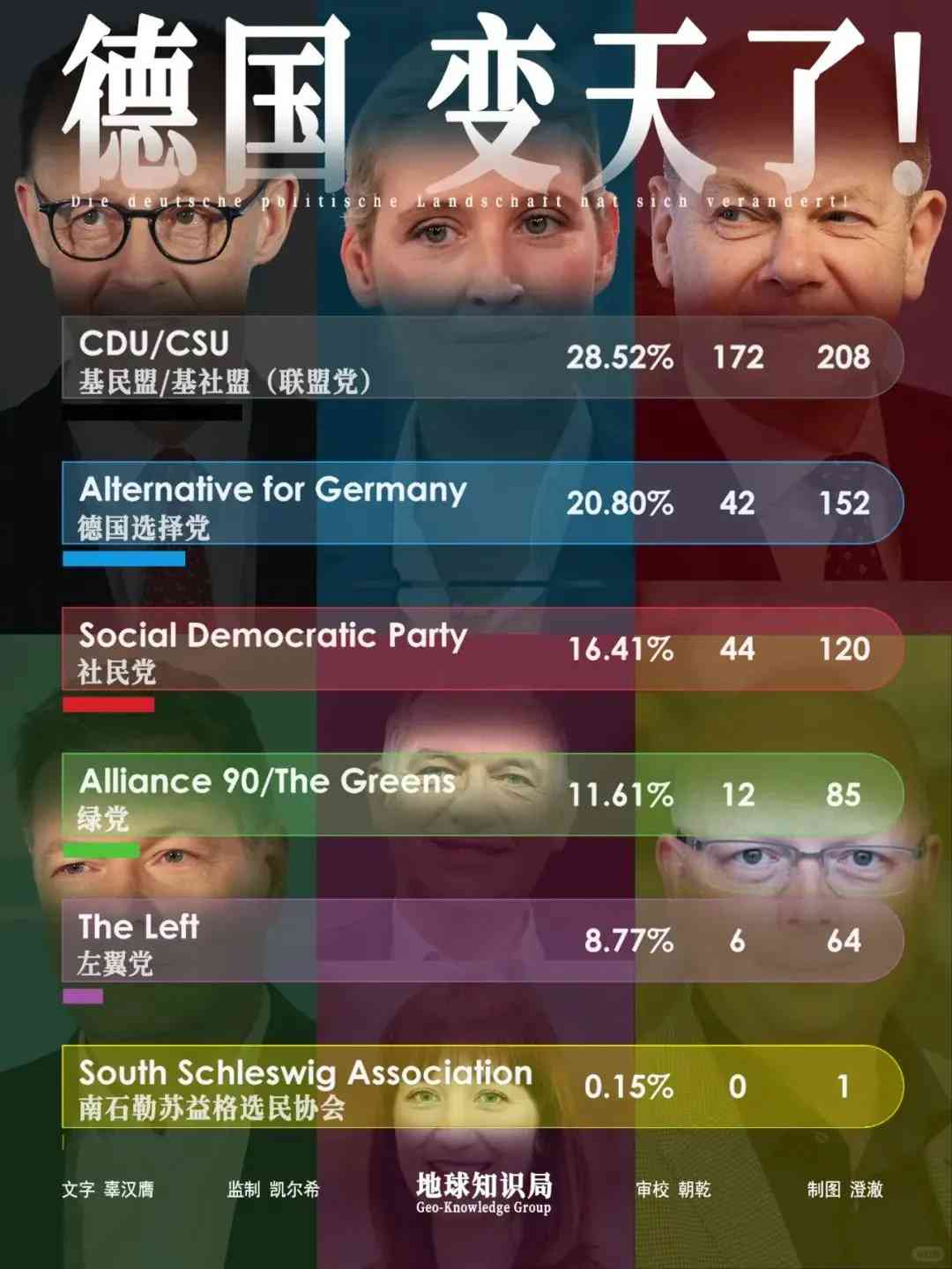

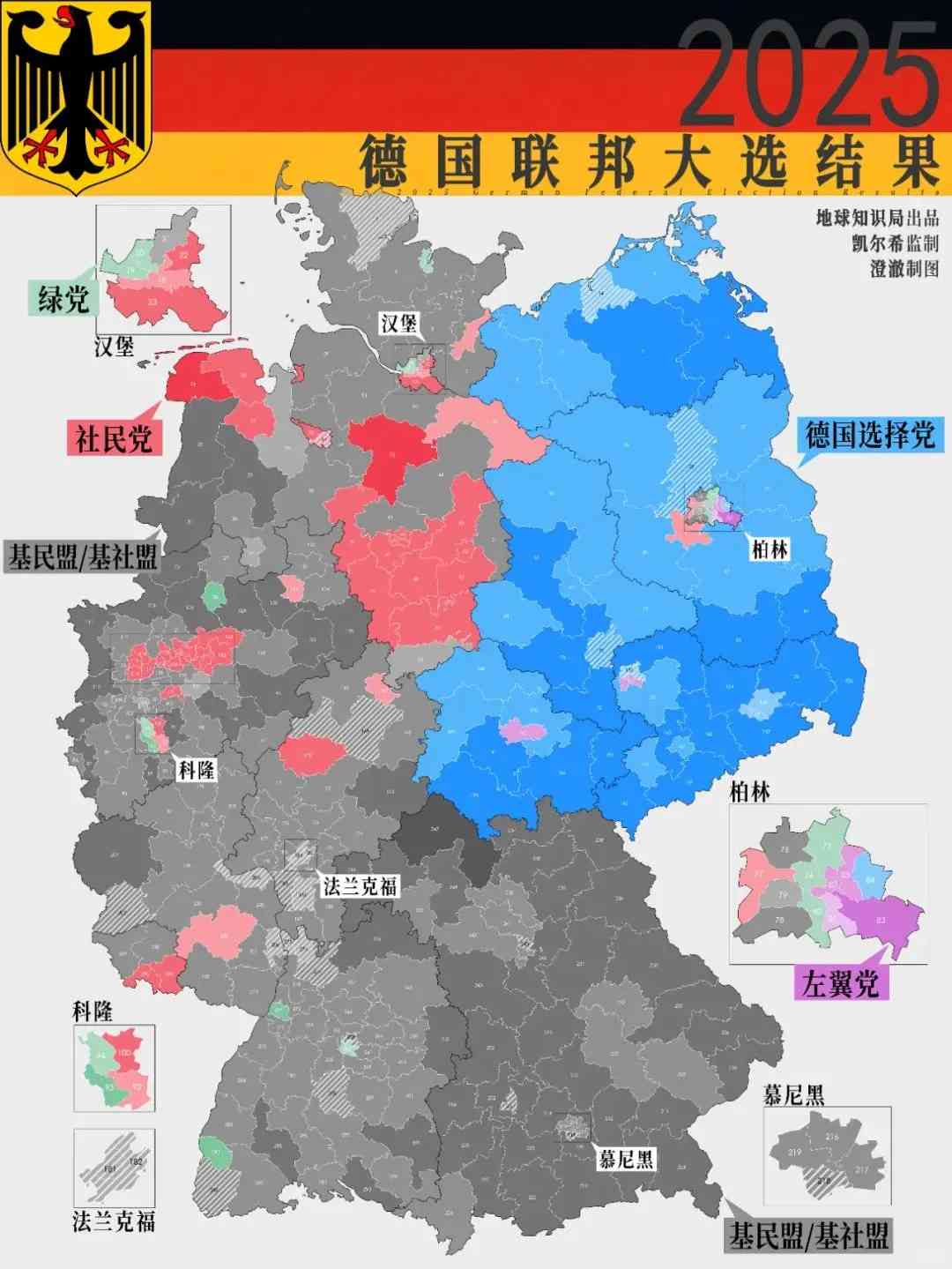

The results of the German federal election have been announced, with the CDU/CSU (Union) reclaiming the top position. Meanwhile, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) has made a historic breakthrough, securing second place as an unexpected “dark horse.” This election not only signals a significant rightward shift in German politics but also highlights the enduring 35-year-old divide between East and West Germany.

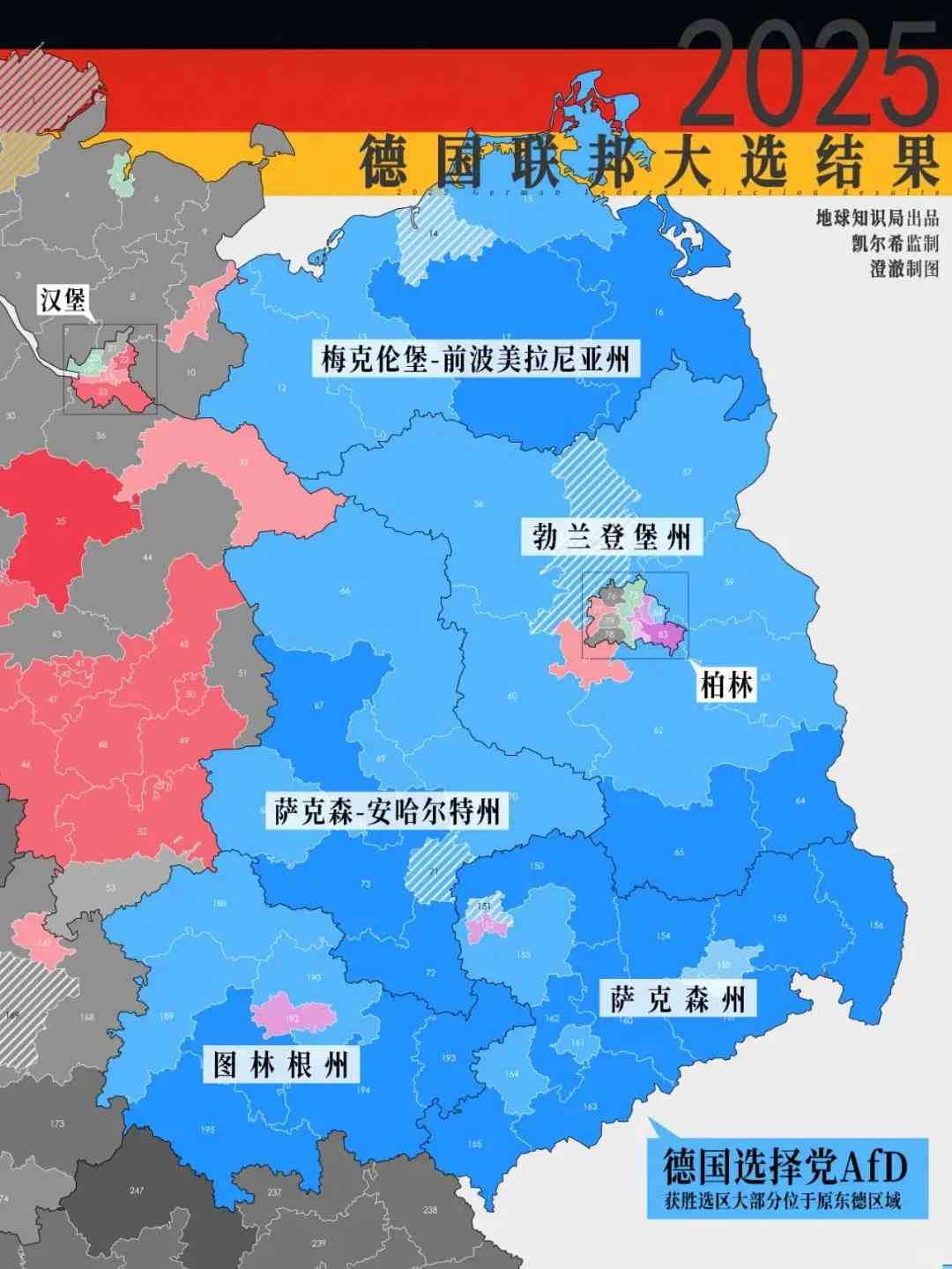

The electoral map shatters the illusion of national unity. In the five states of former East Germany, support for the AfD generally exceeds 30%, while in the West, it hovers around just 5%. This stark contrast reveals deep-seated economic and social disparities.

These divisions reflect glaring economic inequalities and profound social tensions. The average monthly income in the East is 824 euros lower than in the West, and its GDP stands at only 82% of the West’s. Additionally, the aging population rate in the East is 12% higher, and the working-age population is projected to decline by 560,000 to 1.2 million over the next two decades.

Eastern voters feel like second-class citizens, abandoned after reunification. In this election, the AfD has capitalized on the anger of those who feel “left behind,” while the left in the West has fallen into the trap of “value superiority.” Thirty-five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the invisible dividing line has become even more pronounced.

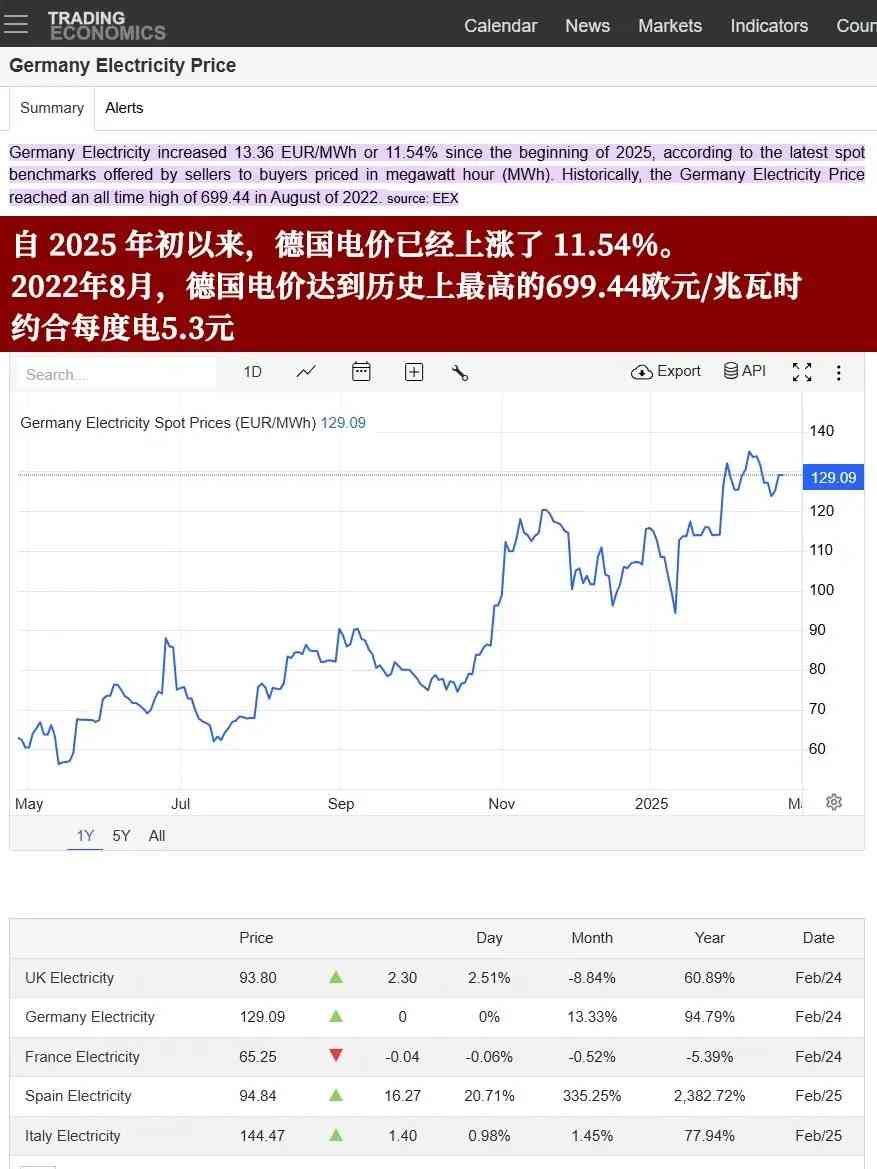

Amid the ongoing energy crisis, soaring electricity prices in the East have further fueled public discontent. AfD leader Tino Chrupalla has called for “restarting nuclear power plants,” striking a chord with industrial workers’ fears about their livelihoods.

The once-promising Green Party has suffered a major setback, receiving only 12.3% of the vote, their worst performance yet. Their environmental agenda is seen by many as a “scythe that takes away jobs”: the energy transition has led to the outflow of industries, and skyrocketing electricity prices have made life unbearable for ordinary families. Eastern voters view the Green Party as a “tool for Western elite charity.”

Despite the AfD’s strong showing, traditional parties are resolute in building a “firewall” against them, firmly stating “no cooperation with the far-right.” However, the AfD could still wield significant influence through parliament, challenging policies on immigration and energy strategy. After all, 20% of public opinion cannot be ignored.

This election marks not the end but the beginning of a political upheaval in Germany. Beneath the right-wing jubilation lies a collective anxiety over economic recession, migration crises, and the erosion of identity.

The division between East and West Germany serves as a mirror, reflecting the deep contradictions in the process of European integration. Anti-globalization and anti-European integration sentiments are rapidly spreading across Europe. Can this divided Germany still support the future of Europe?